Applied core-shamanism overview:

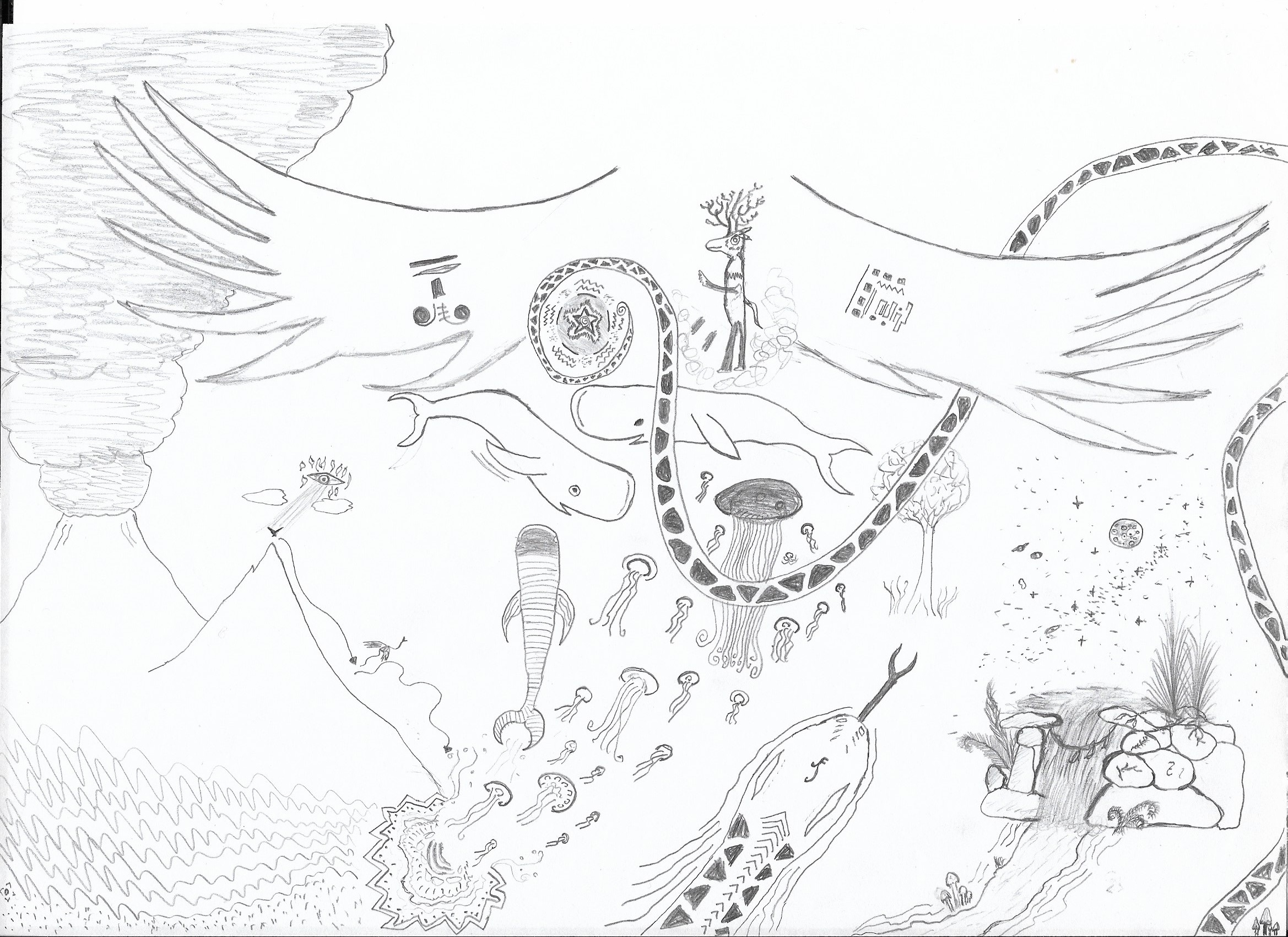

Core-shamanism is an ensemble of techniques and is not attached to any religious dogma. There is no mythology or cosmology imposed and you basically discover your own cosmology by first-hand experience. Core-shamanism focusses in teaching the basic and core elements that are similar across world cultures and inherent to human psyche.

Core-shamanism uses mainly the repetitive drumming sound (dance and chanting are also used) to enter another state of consciousness and journey to other worlds. The journey lasts between 15 to 30 minutes and is done lying with closed eyes. Before undertaking a journey, a clear intention has to be set: “where do I go and for what goal?”.

During the Base Seminar for instance, the main intention is to meet and bond with one of your spirit allies, the Power Animal.

Every experience is unique; people can experience physical sensations, hear sounds and talking, see images, experience strong emotions, etc. Those experiences are meaningful and can be transformative if well integrated in everyday life.

Going into the shamanic state of consciousness is very safe and simple, respecting few rules, as well as the proper set and setting.

A large variety of benefits can come from the shamanic work with power animals or guides like for example: finding guidance, healing, help for addiction, emotional support, enhance connection with nature, positive effect on behaviour, meaning of life, well-being, better relation to people, etc.

Academic overview:

Shamanism is one of the most ancient (probably the most ancient) and universal psycho-socio-spiritual systems of healing and problem solving in communities which has been perfected over millennia of experimentation by shamans (Harner, 2014; Winkelman, 2010). Several accounts point that it dates back at least to the upper Palaeolithic period (40 000 BCE) (Clottes & Lewis-Williams, 2007; Winkelman, 2010) and maybe even earlier (Tedlock, 2005).

Even though the word shamanism is commonly accepted in the academic framework it raises some semantic issues. Taken from the Tungusic language (Siberia) it is now used by the westerners to label every healer that does similar work (Harner, 2012). I would prefer to use it in its plural form, shamanisms, to try to reflect better the multitude of aspects that it entails. The definition of Walsh (1991) is therefore particularly accurate when he talks about shamanism as a “family of traditions” (p.87). We can find traces of shamanic practices all around the world (Harner 2014), some are still alieved and used to heal efficiently. Shamanism has mainly and firstly been studied by anthropologists, who, until more recently, often rejected the efficacy and reality of this phenomenon, and considered shamans as “ministers of the devil”, charlatans and mentally ill peoples (Narby & Huxley, 2009). However, the view on shamanism and shamans has shifted because shamans are now seen by a number of scholars as healers, counsellors and even psychotherapists (Krippner, 2012).

Sonic driving (rattling or drumming) is the most used technique in the world in indigenous contexts to enter into a non-ordinary state of consciousness (NOSC) or shamanic state of consciousness (SSC) Harner (2014).

Core-shamanism is the term used by the Foundation for shamanic studies (FSS) created by Michael Harner (in memoriam 1929-2018) to describe their type of shamanism. Harner derived a western adaptation of shamanism including universal or core element found in indigenous context (drumming, etc..).

The repetitive sound of the drum causes a theta synchronisation pattern in the brain (Neher, 1962) and thus induces the SSC (Harner, 2012). The SSC is a transcendent state which the shaman/person enters deliberately to accomplish a precise serious work. It involves the knowledge of the objectives of the practice of shamanism, that are for example necessary for healing (Harner, 2014). Narby & Huxley (2009) stated that the SSC offers the possibility of journeying in other realms with a wide array of experiences including the possibility of seeing, hearing, feeling, knowing, etc. things that would not be possible in an ordinary state of consciousness (OSC). This technique has been shown to be non-harmful even for beginners when an appropriate set and setting are respected (Schmitz, 2009).

During the shamanic journey the traveller is most likely to encounter spirits. A particular kind of spirit encountered is called a power animal (PA). Core-shamanism is based on a quasi-universally shared shamanic cosmology of the three spiritual worlds (Lower, middle and Upper; Walsh, 1991). Power animals are spirits belonging to the lower world. Those spirits, as well as the guides from the upper world are benevolent spirits, which means that they are genuinely wanting to help the experiencer (Chambon & Huguelit, 2010). The power animal is often the most important spirit for a shaman/person, and is not limited to one by person/shaman. Power animals are essential allies and assist the person/shaman in many ways in their journey for example during healings, soul retrievals, shamanic extractions, power animal retrievals, divinations, etc. (Ingerman, 2007; Huguelit, 2012).

If you want to dive more into it you will find a small selection of books, articles and film on this site: Books, Links, and More.

References:

Chambon, O., & Huguelit, L. (2012). Le Chamane & le Psy : Un dialogue entre deux mondes. Mama Editions.

Clottes, J., & Lewis-Williams, D. (2007). Les chamanes de la préhistoire : Transe et magie

dans les grottes ornées Suivi de Après Les Chamanes, polémiques et réponses. Points.

Harner, M. (2012). La voie du chamane: Un manuel de pouvoir & de guérison. MamaEditions.

Harner, M. (2014). Caverne et cosmos – Rencontres chamaniques. MamaEditions.

Huguelit, L. (2012). Les huit circuits de conscience : chamanisme cybernétique & pouvoir créateur. Mama Editions.

Ingerman, S. (2007). Recouvrer son âme et guérir son moi fragmenté. Editeur Guy Tredaniel.

Krippner, S. (2012). Shamans as healers, counselors, and psychotherapists. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 31(2), 9.

Narby, J., & Huxley, F. (2009). Anthologie du chamanisme : Cinq cents ans sur la piste du savoir. Editions Albin Michel.

Neher, A. (1962). A physiological explanation of unusual behavior in ceremonies involving drums. Human biology, 34(2), 151-160.

Tedlock, B. (2005). The woman in the shaman’s body: Reclaiming the feminine in religion and medicine. Bantam.

Schmitz, S. (2009). The therapeutic use of the shamanic journey: Lived experience and psychospiritual outcomes of learning an ancient spiritual practice (Doctoral Dissertation, Institute of Transpersonal Psychology). Pro Quest. (AAI3369613).

Walsh, R. (1991). Shamanic cosmology: A psychological examination of the shaman’s worldview. ReVision, 13(2), 86-100.

Winkelman, M. (2010). Shamanism: A biopsychosocial paradigm of consciousness and healing. ABC-CLIO.